#zhubin li

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

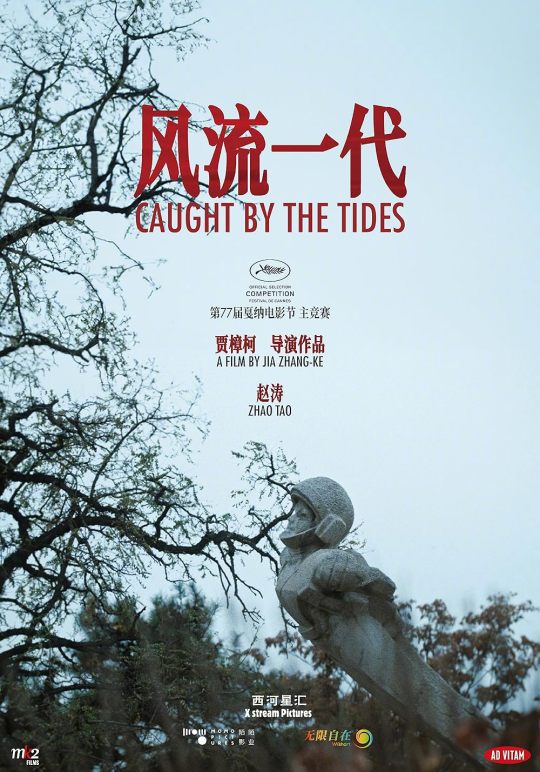

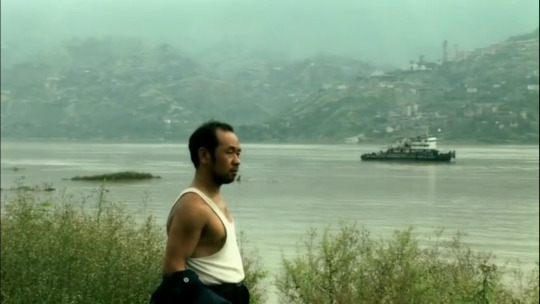

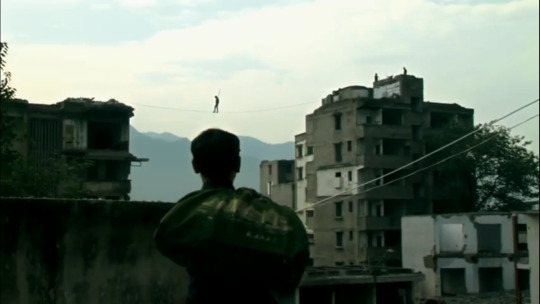

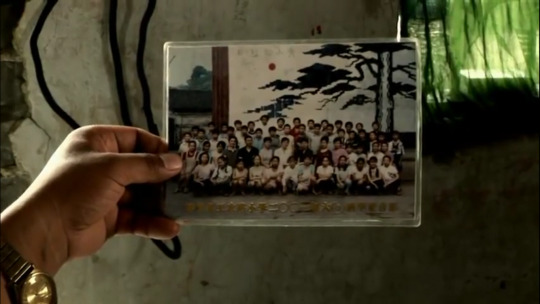

Caught by the Tides (2024)

Dir. Jia Zhangke

#caught by the tides#film#movie#drama#asian cinema#cinema#asian film#romance#chinese#chinese cinema#jia zhangke#zhao tao#zhubin li#pan jianlin#zhou you#zhou lan#ren ke#mao tao#china#datong#surreal#experimental film

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caught by the Tides (Feng liu yi dai), Zhangke Jia (2024)

#Zhangke Jia#Jiahuan Wan#Tao Zhao#Zhubin Li#Eric Gautier#Nelson Lik wai Yu#Giong Lim#Matthieu Laclau#Yang Chao#Xudong Lin#2024

0 notes

Text

Caught by the Tides (2024) | dir. Jia Zhangke

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the Films in Competition at Cannes, Ranked from Best to Worst

The twenty-two films that premièred in the 2024 festival’s main program offered much to savor and revile.

By Justin Chang May 26, 2024

The seventy-seventh annual Cannes Film Festival came to a startling and joyous conclusion on Saturday night, when the competition jury, chaired by Greta Gerwig, awarded the Palme d’Or, the festival’s highest honor, to “Anora,” a funny, harrowing, and finally quite moving portrait of a sex worker’s madcap New York misadventures. It was startling because the movie, though one of the best-received in the competition, had not been widely tipped for the top prize, which seldom goes to a U.S. film; with “Anora,” Sean Baker becomes the first American director to win the Palme since Terrence Malick did, for “The Tree of Life” (2011), thirteen years ago. And it was joyous not only because the award was bestowed on a worthy and remarkable film but because Baker used the occasion to deliver the best, most eloquent and impassioned acceptance speech I’ve ever heard a Palme winner give.

Reading from prepared remarks, Baker singled out two other filmmakers in the competition, Francis Ford Coppola and David Cronenberg, as among his personal heroes. He dedicated the award to sex workers everywhere, a fitting tribute from a filmmaker who has put their lives front and center, with drama, humor, and empathy, in movies like “Starlet” (2012), “Tangerine” (2015), and “Red Rocket” (2021). He tossed some exquisite shade in the direction of the “tech companies” behind the so-called streaming revolution—including, presumably, Netflix, which came away as one of the night’s big winners; its major acquisition of the festival, Jacques Audiard’s musical “Emilia Pérez,” won two prizes. And, in a moment that drew rapturous applause, Baker delivered a plea on behalf of theatrical films, declaring, “The future of cinema is where it started: in a movie theatre.”

I was fortunate to see all twenty-two films in the Cannes competition on the big screen, projected under superior conditions in houses packed with fellow movie lovers. It’s my hope that, when these movies are released in the U.S., as the great majority of them likely will be, you will seize the chance to see them on the big screen as well—even “Emilia Pérez,” which Netflix may not keep in theatres for long, but whose bold dramatic and stylistic risks have the best chance of winning you over if they have your undivided, wide-awake attention.

I have ranked the movies in order of preference, from best to worst. Here they are:

1. “Caught by the Tides”

Jia Zhangke, a Cannes competition veteran, has long been the cinema’s preëminent chronicler of modern China (“Mountains May Depart,” “Ash Is Purest White”), mapping its social, cultural, and geographical complexities with great formal acumen, and also with the longtime collaboration of his wife, the superb actress Zhao Tao. Jia’s latest work, drawing on an archive of footage shot in the course of roughly two decades, unfurls a story in fragments, about a woman (Zhao) and a man (Li Zhubin) who fall in love, bitterly separate, and have a melancholy reunion years later. It’s an achievement by turns fleeting and monumental: a series of interlocking time capsules, a wrenching feat of self-reflection, and a stealth musical, in which Zhao dances and dances, standing in for millions who have learned to sway and bend to history’s tumultuous beat.

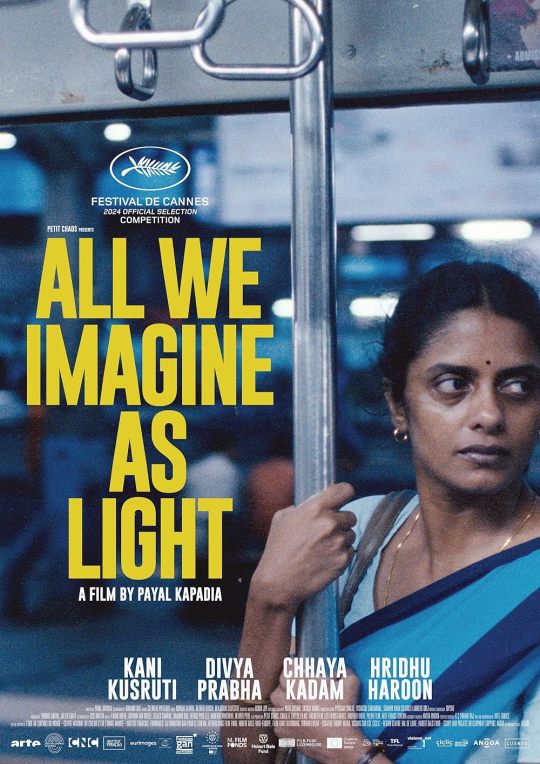

2. “All We Imagine as Light”

As the first Indian feature invited to compete at Cannes in nearly three decades, Payal Kapadia’s narrative début (after her 2021 documentary, “A Night of Knowing Nothing”) would be notable enough; that the movie is so delicately felt and sensuously textured is cause for outright celebration. Winner of the festival’s Grand Prix, or second place, it tells the story of two roommates, Prabha (Kani Kusruti) and Anu (Divya Prabha), who work as nurses at a Mumbai hospital. It teases out their personal circumstances—Prabha’s estrangement from her unseen husband, Anu’s frowned-upon romance with a young Muslim man (Hridhu Haroon)—with a quiet truthfulness that, like the glittering lights of the city, lingers expansively in the memory. (A forthcoming Sideshow/Janus Films release.)

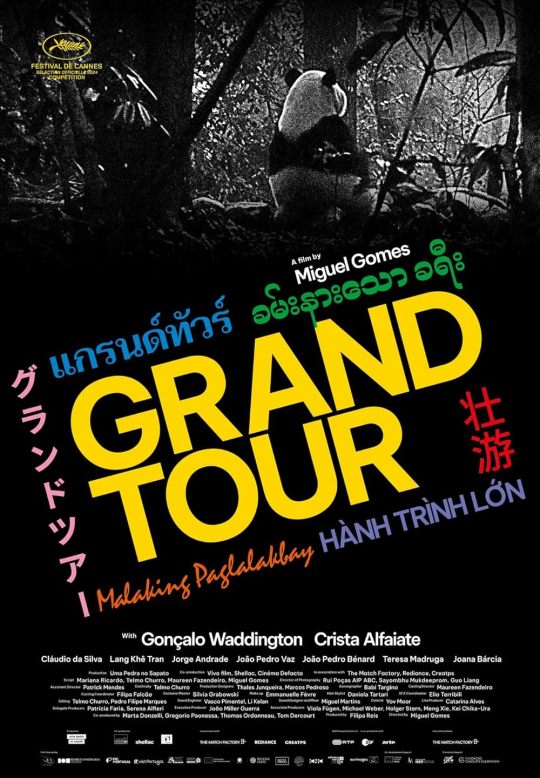

3. “Grand Tour”

The Portuguese director Miguel Gomes (“Tabu,” “Arabian Nights”) delivered some of the most virtuosic filmmaking in the competition—as the jury recognized by giving him the Best Director prize—with this characteristically yet extraordinarily playful colonial-era travelogue. Shifting between color and black-and-white, set in 1917 but full of fourth-wall-breaking anachronisms, the movie tells a story of sorts about a roving British diplomat (Gonçalo Waddington) and a fiancée (Crista Alfaiate) he’s in no hurry to marry. But its true fascination lies in the humid atmosphere and wanderlust-inspiring splendor of its East and Southeast Asian locations, ranging from Singapore and Bangkok to Shanghai and Rangoon. It’s a movie to get lost in.

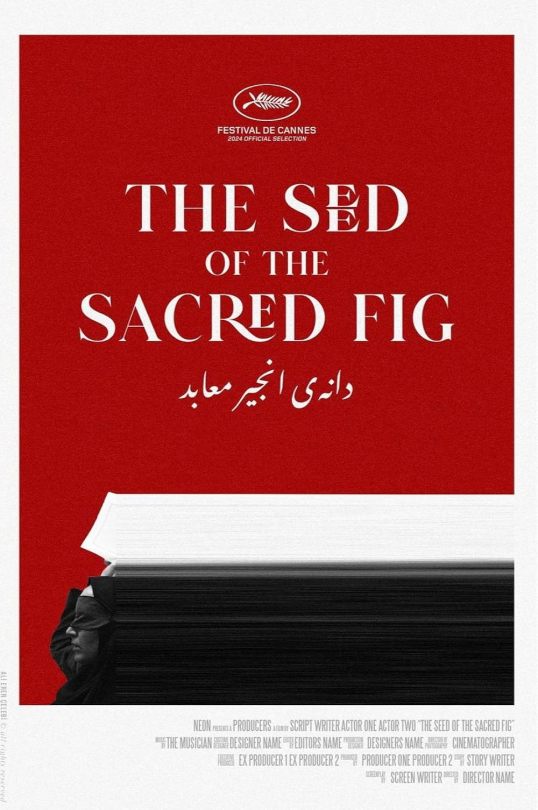

4. “The Seed of the Sacred Fig”

It’s impossible to absorb this blistering domestic drama without thinking of its dissident director, Mohammad Rasoulof, who recently fled Iran after being sentenced to prison and a flogging. (His appearance at his film’s première made for one of the most emotional moments in recent Cannes memory.) Shot entirely in secret, the story follows a Tehran-based husband (Missagh Zareh) and wife (Soheila Golestani) who are increasingly at war with their progressive-minded young-adult daughters (Mahsa Rostami, Setareh Maleki) during nationwide political protests led by women. The result is a thriller of propulsive skill and blunt emotional force, marrying the muscularity of an action film to the psychological intensity of a chamber drama. (A forthcoming Neon release.)

5. “Anora”

The director Sean Baker is near the height of his storytelling powers with this dazzling (and now Palme d’Or-winning) portrait of a Manhattan strip-club dancer (a revelatory Mikey Madison) who impulsively marries the ultra-spoiled son (Mark Eydelshteyn) of a Russian oligarch. Much comic chaos ensues, some of it pushed past the brink of plausibility, but Baker’s multifaceted love for his characters proves infectious and sustaining, as does his belief that acts of unexpected kindness can redeem even the darkest nights of the soul. (A forthcoming Neon release.)

6. “The Shrouds”

Early on in this elegantly sombre yet mordantly funny new movie, which stars Vincent Cassel, Diane Kruger, and Guy Pearce, the director David Cronenberg, a master of cerebral horror, unveils his latest invention: a technologically advanced burial shroud that allows people to watch a loved one’s body decomposing in the grave. So begins a drolly fluid inspection of classic Cronenberg themes—the deterioration of the flesh, the instability of the image, the paranoia-inducing incursions of technology into every aspect of life—but imbued with a nakedly personal dimension that the director has noted in interviews; the story was inspired by his wife’s death, in 2017, from cancer.

7. “Megalopolis”

In this legendarily long-gestating passion project, which I’ve written about at length, Francis Ford Coppola posits that our fragile, battered civilization is headed the way of the Roman Empire. The grimness of that prospect is unsurprising from a director accustomed to peering deep into the heart of American darkness (the “Godfather” movies, “The Conversation,” “Apocalypse Now”). For all that, the filmmaking here glows with a particularly hard-won optimism, even a welcome sense of play—borne out by an ensemble of actors, including Adam Driver, Giancarlo Esposito, and especially Aubrey Plaza, who fully embrace Coppola’s rhetorical and conceptual flights of fancy.

8. “The Substance”

Sympathetic or sadistic? Feminist or misogynist? Coralie Fargeat’s body-horror bonanza, which won the festival’s award for Best Screenplay, has been one of the competition’s more polarizing hits, which is unsurprising; divisiveness should be expected from a story about an aging actress and TV fitness guru who, desperate to regain her youthful bod of yesteryear, effectively splits herself in two. Whether the outlandish premise (think “The Picture of Dorian Gray” by way of “Death Becomes Her”) and its blood-gushing fallout withstand intellectual scrutiny, there’s no doubting the ferocity of the two leads, Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley, or Fargeat’s sheer filmmaking verve as she pushes her ideas to their sanguinary conclusions.

9. “Motel Destino”

Just a year after the Brazilian director Karim Aïnouz appeared in competition with a surprisingly stiff-corseted English period drama, “Firebrand,” it was bracing to watch him rebound with the competition’s most sexually uninhibited and flagrantly horny title; corsets don’t apply here, and even underwear proves blissfully optional. Set at a seedy roadside motel where the clientele never stops moaning, it’s a feverishly shambling erotic thriller starring three very game actors (Iago Xavier, Nataly Rocha, and Fábio Assunção) in a romantic triangle that plays like James M. Cain with sex toys—“The Postman Always Cock Rings Twice,” as it were.

10. “Emilia Pérez”

A trans-empowerment musical set against the backdrop of Mexico’s drug cartels might sound like a dubious proposition on paper, and, for the many detractors of this genre-melding big swing from the French director Jacques Audiard (“A Prophet,” “The Sisters Brothers”), what actually made it onto the screen was no better. But I was disarmed from the start by Audiard’s quasi-Almodóvarian vibes, his touchingly imperfect embrace of song-and-dance stylization, and, most of all, his three leads: the remarkable discovery Karla Sofía Gascón, a scene-stealing Selena Gomez, and a never-better Zoe Saldaña. All three (along with Adriana Paz) were recognized with the festival’s Best Actress prize, awarded collectively to the movie’s ensemble of actresses; Audiard also won the Jury Prize. (A forthcoming Netflix release.)

11. “Oh, Canada”

After a tense trilogy of dramas about male redemption through violence (“First Reformed,” “The Card Counter,” “Master Gardener”), the writer and director Paul Schrader has taken a gentler turn with an adaptation of “Foregone,” a 2021 novel by the late Russell Banks. (It’s his second Banks adaptation, after the 1997 drama “Affliction.”) In exploring the fragmented consciousness of an aging documentary filmmaker (played at different ages by Richard Gere and Jacob Elordi), Schrader bravely forsakes the narrative fastidiousness of his recent work and takes on grand themes of memory, mortality, and artistic self-reckoning, to formally ragged but sincerely moving effect.

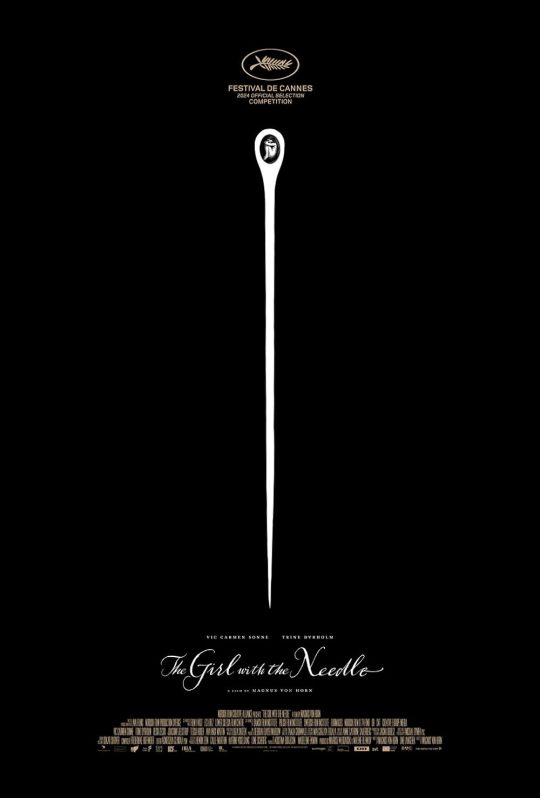

12. “The Girl with the Needle”

This stark and terrifying black-and-white drama from the Swedish-born, Polish-based director Magnus von Horn (“Sweat”) was perhaps the competition’s bleakest entry. Set in Copenhagen immediately after the First World War, it pins us so mercilessly to the hard-bitten perspective of Karoline (an excellent Vic Carmen Sonne), a factory seamstress who becomes pregnant out of wedlock, that we scarcely notice her story shifting in a different, more sinister direction. It’s a bitterly hard-to-stomach brew of a movie, at once hideous and beautifully made, with a chilling supporting turn by Trine Dyrholm as a friend whose interventions turn out to be anything but benign.

13. “Three Kilometres to the End of the World”

The setting of this well-observed but emotionally opaque drama, from the Romanian actor turned director Emanuel Pârvu, is a small rural village where a closeted teen-age boy, Adi (Ciprian Chiujdea), is brutally beaten after being caught in an intimate moment with a male traveller. Pârvu teases out the legal, psychological, and moral fallout with the pitch-perfect performances and laserlike formal focus that have become hallmarks of new Romanian cinema. But, though the movie is persuasive enough as an indictment of small-town religious fundamentalism and homophobia, it proves curiously incurious about Adi’s perspective, to the detriment of its own human pulse.

14. “Kinds of Kindness”

After his Oscar-winning period romps “The Favourite” (2018) and “Poor Things” (2023), the Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos scales back—but goes long—with a sprawling, increasingly tedious compendium of comic cruelty. My favorite of the film’s three disconnected stories, all featuring the same actors, is the one where Jesse Plemons (the ensemble M.V.P., as the jury recognized with its Best Actor award) plays Willem Dafoe’s Manchurian candidate; my least favorite is the one where Emma Stone joins a sweat-worshipping sex cult. The one where Stone slices off her finger and cooks it for Plemons falls—much like the movie in Lanthimos’s over-all œuvre—somewhere in the middle. (A Searchlight Pictures release, opening June 21st in theatres.)

15. “Bird”

My admiration for the English filmmaker Andrea Arnold (“American Honey”) is such that I’m eager to revisit her latest rough-and-tumble coming-of-age story and find that I undervalued it. Arnold is certainly skilled at integrating recognizable actors, which in this case includes Barry Keoghan and Franz Rogowski, into her grottily realist frames, and she has an appealing lead performer in Nykiya Adams, as a twelve-year-old girl who overcomes persistent abuse and neglect. But the story may lose you—as it lost me—with a magical-realist turn that magnifies, rather than minimizes, the tortured-animal symbolism that has often dogged Arnold’s work.

16. “Beating Hearts”

An exchange of insults at a high-school bus stop provides a saucy meet-cute for a good girl (Mallory Wanecque) and a ne’er-do-well boy (Malik Frikah); so begins a raucous and endearing love story for the ages, in which the director Gilles Lellouche, with outsized glee and little discipline, merrily appropriates the conventions of classic Hollywood musicals and gangster flicks. The result is much too long at nearly three hours—the story spans several years, with Adèle Exarchopoulos and François Civil playing older versions of the two leads—but I can’t say I didn’t warm to its rambunctious cornball charm.

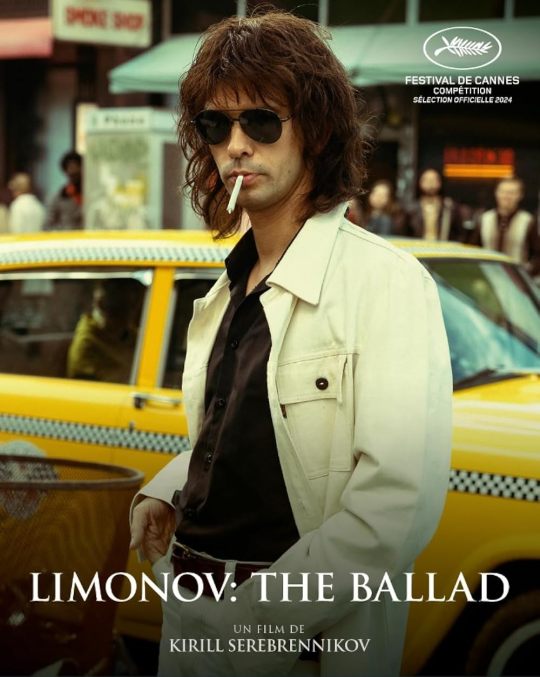

17. “Limonov: The Ballad”

Why make a film about Eduard Limonov, the globe-trotting Russian dissident poet and punk provocateur reviled for his pro-fascist sympathies? The filmmaker Kirill Serebrennikov never musters a satisfying answer in this muddled English-language bio-pic, despite an energetically uninhibited central performance by Ben Whishaw and a cheeky panoply of filmmaking techniques—jittery camerawork, lengthy tracking shots—meant to catch us up in the épater-la-bourgeoisie exuberance of Limonov’s revolt. Considering his earlier work, I prefer the rebel-youth vibes of “Leto” (2018) and the dazzling cinematic assaults of “Petrov’s Flu” (2021), both of which also screened in competition here.

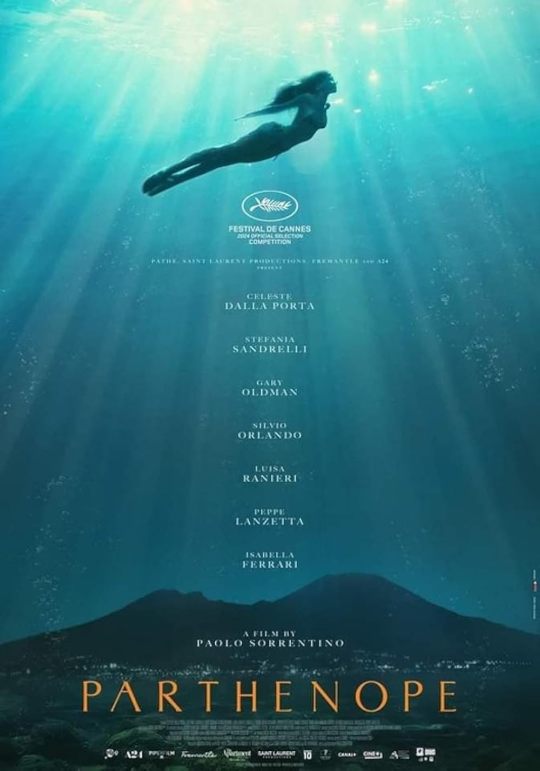

18. “Parthenope”

Nearly every new picture from the Italian auteur Paolo Sorrentino could be reasonably called “The Great Beauty,” the title of his gorgeous 2013 cinematic tour of Rome. (It left that year’s Cannes empty-handed, but won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film.) His latest work remains most intriguing for its ambivalent but still sensually overpowering vision of the director’s home town, Naples, from which springs a modern-day goddess, named after Parthenope, a Siren from Greek mythology. She’s played by Celeste Dalla Porta, a great beauty indeed and an empathetic screen presence, though only fitfully does her character seem worthy of this movie’s epic enshrinement.

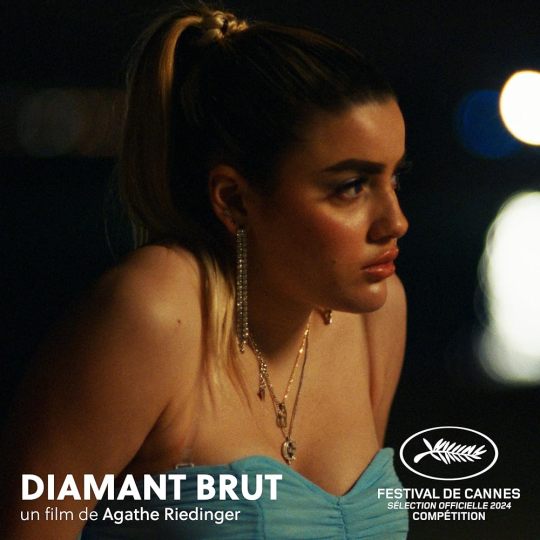

19. “Wild Diamond”

Another disquisition on beauty and its discontents, this time from the débuting French writer and director Agathe Riedinger. She hurls us the life and busy social-media feed of a nineteen-year-old, Liane (a terrific Malou Khebizi), who has nipped, tucked, and tailored every part of herself to realize her dream of being selected for a hot new reality-TV series. Part influencer-culture cautionary tale, part bad-girl Cinderella story, the movie glancingly suggests the soul-rotting effects of beauty worship, but it falls victim to the trap that Liane is trying to avoid: in a sea of worthy candidates, it doesn’t especially stand out.

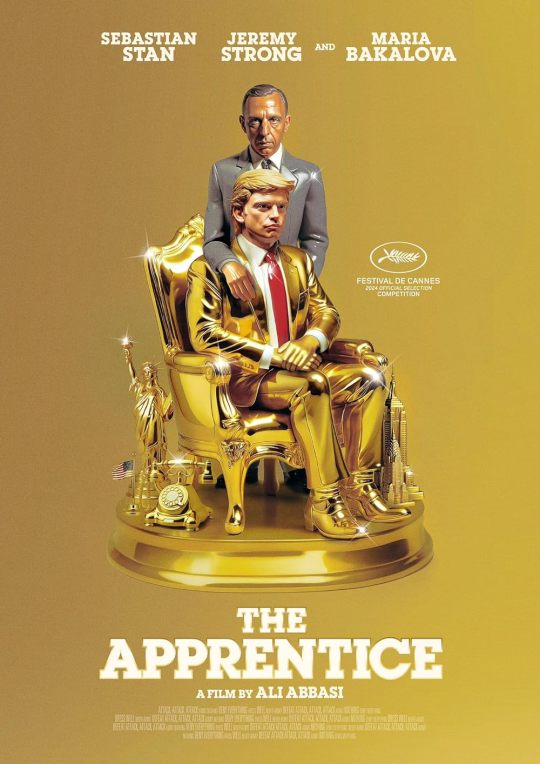

20. “The Apprentice”

Donald Trump’s attorneys have threatened legal action to block the release of this drama about his early rise to fame and wealth under the mentorship of the attorney Roy Cohn (Jeremy Strong). It speaks to the useless proficiency of Ali Abbasi’s movie that the prospect of such censorship provokes more indifference than outrage. Shot to evoke cruddy nineteen-eighties VHS playback, the movie is well acted by Strong, Maria Bakalova as Ivana Trump, and an increasingly makeup-buried Sebastian Stan as Trump himself, depicted from the start as a sack of shit that gets progressively shittier. It’s not dismissible, but it’s hardly the stuff of revelation, either.

21. “Marcello Mio”

In this trifling meta-comedy from the French filmmaker Christophe Honoré (previously in the 2018 Cannes competition with the lovely “Sorry Angel”), the actress Chiara Mastroianni embarks on a strainedly whimsical personal odyssey to examine the legacy of her late father, the legendary Italian actor Marcello Mastroianni, and her own conflicted place therein. To that end, she spends much of this overstretched movie in “8½” and “La Dolce Vita” black-suited drag as she navigates a roundelay of industry in-jokes; among the French cinema luminaries making appearances are Fabrice Luchini, Nicole Garcia, and, most welcome, Chiara’s mother, Catherine Deneuve.

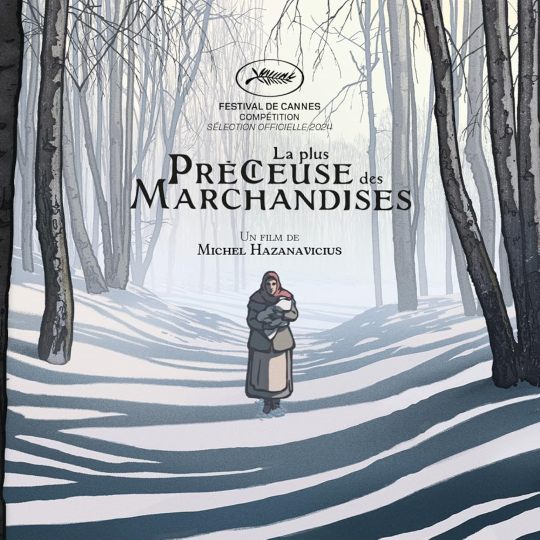

22. “The Most Precious of Cargoes”

The French director Michel Hazanavicius continues his uneven post-“The Artist” run with this animated Second World War fable, adapted from a 2019 novel by Jean-Claude Grumberg (and narrated by the late Jean-Louis Trintignant). It has an affecting opening stretch, in which a baby girl, thrown by her desperate father from an Auschwitz-bound train, is rescued and raised in secret by a woodcutter’s kindhearted wife. But when the child’s provenance is discovered, stoking local antisemitism, the movie becomes a bathetic wallow in Holocaust imagery, drowned in an Alexandre Desplat score whose every surge turned my heart increasingly to stone. ♦

#Cannes Film Festival#Cannes Film Festival 2024#Youtube#Caught by the Tides#All We Imagine as Light#Grand Tour#The Seed of the Sacred Fig#Anora#The Shrouds#Megalopolis#The Substance#Motel Destino#Emilia Pérez#Oh Canada#The Girl with the Needle#Three Kilometres to the End of the World#Kinds of Kindness#Bird#Beating Hearts#Limonov: The Ballad#Parthenope#Wild Diamond#The Apprentice#Marcello Mio#The Most Precious of Cargoes

108 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Caught by the tides - de l'influence de Wang Bing

Un film de Jia ZhangkeAvec: Zhao Tao, 周遊, Ren Ke, Mao Tao, Zhubin Li, Pan Jianlin, Zhou LanChine début des années 2000. Qiaoqiao et Bin vivent une histoire d’amour passionnée mais fragile… Notre avis: ***

Retrouvez l'article complet ici https://lemagcinema.fr/microcritique/caught-by-the-tides-de-linfluence-de-wang-bing/

0 notes

Photo

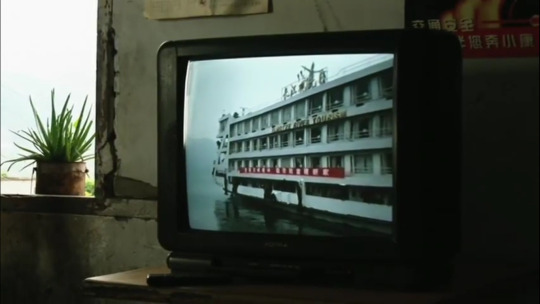

Still Life (2006)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Commentary on the Water Classic: Yanqi and the Puchang Sea

[The north-eastern Tarim states]

(Yanqi)

The Great He大河 again goes east, and on its right side meet up with the river of Dunhong敦薨. Its river sets out north of Yanqi焉耆 from the mountain of Dunhong敦薨. It is west of the Xiongnu, and east of the Wusun烏孫.

The Classic of Mountains and Seas says: The mountain of Dunhong敦薨, the river of Dunhong敦薨 sets out from there, and flows wests to pour into You Marsh泑澤. It sets out from the north-eastern corner of Kunlun崑崙, in truth it is nothing but the source of the He河.

The two sources have a path in common. The western source flows east and divideds to become two rivers. The left river flows south-west, sets out to the west of Yanqi焉耆, passes to flow past the wilderness of Yanqi焉耆, bends and flows south-east, and pours into the shoreline of Dunhong敦薨. The right river flows south-east, and again divides to become two rivers. Left and right are in the state of Yanqi焉耆. The city resides in the middle of the four rivers, and is an island of the He River河水. It is seated at Yunqu City員渠城. The distance west to Wulei is 400 li. To the south meets up the pair of rivers, and they pour together into the riverbank of Dunhong敦薨.

The eastern source flows south-east and divides to become two rivers. The ravine surges to draw both forth, vast rapids deeply issues out, and together they flow south-east, to pass and set out east of Yanqi焉耆, and lead to west of Weixu State危須國. The state is seated at Weixu City危須城. The distance west to Yanqi焉耆 is 100 li. Again it flows south-east, and pour into the fens of Dunhong敦薨. With the streams' flows adding up, the mountain pools' water then rises, overflows and becomes a sea.

The Historical Records says: In the sea nearby Yanqi焉耆 there is much fish and birds. To the north-east separated by great mountains, it connects with Jushi車師.

The river of Dunhong敦薨 from the Western Sea passes Weili State尉犂國, the state is seated at Weili City尉犂城. The distance west to to where the Chief Protector was seated is 300 li, the distance north to Yanqi焉耆 is 100 li.

Its river again goes west to set out from Sha Mountain's沙山 [“Sand Mountain”] Tieguan Valley鐵關谷 [“Iron Pass Valley”]. Again it goes south-west, and passes continuous cities separately focused on, and breaks up to be used for farmlands. Sang Hongyang says: “Your Subject foolishly considers that from the continuous cities and westwards there can be dispatched guarded farms, and so overawe the western states.” Precisely this place.

(Quli)

Its river again bends and flows south, and passes west of Quli State渠犂國. For that reason when the Historical Records says “To the west is a great river大河,” it is precisely this river. Again it flows south-east, and passes Quli State渠犂國, seated at Quli City渠犂城. The distance north-west to Wulei烏壘 is 330 li. When Emperor Wu of Han communicated with the Western Regions, and guarded Quli渠犂 it was precisely this place. To the south it is connected with Jingjue精絶, and to the the north-east it is connected with Weili尉犂. Again it flows to pour into the He河.

The Classic of Mountains and Seas says: The river of Dunhong敦薨 flows west to pour into the You Marsh泑澤. Perhaps where the chaotic He's flows concentrate from the south-west-

The He River河水 again goes east to pass south of Moshan State墨山國, seated at Moshan City墨山城. The distance west until Weili尉犂 is 240 li. The He River again goes east to pass south of Zhubin City注賓城. Again east it passes south of Loulan City樓蘭城, and pour east. Perhaps where they sent out to be defended by farming soldiers, for that reason the city yielded the state's name, and that is all [?].

(Puchang Sea)

The He River河水 again goes east to pour into the You Marsh泑澤, precisely what the Classic speaks of as the Puchang Sea蒲昌海. The water piles up north-east of Shanshan鄯善, and south-west of Long City龍城 [“Dragon City”].

Long City龍城 is the old ruins of Jianglai姜賴, a great state of the Hu. The Puchang Sea蒲昌海 overflowed, and scoured and overturned their state. The city's foundations still exist and are very great. Issue out from the western gate in the morning, and you arrive at the eastern gate in the evening. From the irrigation ditches on its steep banks the remnant run-off blows in the wind, slightly forming the image of a dragon facing west towards the sea. Because of that it is named Dragon City龍城. The land is 1 000 li broad, everywhere it is salty, and is tough and hard. A traveller who was passing by, his livestock and property all laid down on cloth or felt, dug up beneath them. There was a great piece of salt, square like a huge pillow, and then the next one after another. A kind of fog rises up and clouds float, and it is rare to see stars or the sun. There are few birds and many ghosts and oddities. To the west it connects with Shanshan鄯善, to the east it is continuous with the Three Sands三沙, and it is the northern limit of the Sea. For that reason Puchang蒲昌 also has the designation of Salt Marsh鹽澤.

The Classic of Mountains and Seas says: The mountain of Buzhou不周 to the north looks at the mountain of Zhupi諸毗 and overlooks that mountain of Yuechong岳崇. To the east it looks at You Marsh泑澤 from where the He River河水 goes underground. Its source is rolling and roiling rippling and rushing.

The distance east to Yumen玉門 and Yang Passes陽關 is 1 300 li, its breadth and width is 400 li. Its water is clear and still, winter or summer it does not decrease. Within it whirlpools and rapids change in a flash and become the veins of the hidden and submerged, it is the top of the vortex flow. Among the flying birds who spread their feathers within the sky there are none which do not fall down into the abyssal surf. It is precisely from where the He River河水 goes underground and sets out for Jishi積石.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Still Life (2006)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Commentary on the Water Classic: Yutian & Shanshan

[The southern Tarim states, the most important of them being Yutian and Shanshan.

During this time period Yutian (Khotan) was famous as a centre for Buddhist learning.

The submission of Weituqi of Shanshan is recorded in the Hanshu.

Wikipedia says Suo Mai moved to Shanshan in 260 AD, however I could not find the source for this.

The commentary seems to describe a southern river running through the southern states in parallell with a northern river running through the northern states (described in the next part of the commentary). However such a southern river does not (and did not) exit. The rivers referred to here as the "Congling He" and the "Yutian He" go north and becomes the northern river.

One of its sources sets out from mountains south of Yutian state于闐國, and flows north to combine with the He that sets out from Congling蔥嶺. Again east, it pours into the Puchang Sea蒲昌海[2].

(Yutian)

[2]The He River河水 again goes east and combines with the Yutian He于闐河. Southward to the source leads to a mountain south of Yutian南山, customarily spoken of as Choumazhi仇摩置. From Zhi置 it flows north and passes west of Yutian State于闐國, seated at the Western City西城[xicheng]. The ground has many jade stones.The distance west to Pishan皮山 is 380 li. The distance east to Yang Pass陽關 is more than 5 000 li.

Shi Faxian travelled south-west from Wudi烏帝 [error for Wuyi烏夷]. On the roads there were no people. Sand travel is demanding and difficult, and to the hardships from going past there, there are among people's arrangements no comparisons. They were on the road for a month and five days, and then reached Yutian于闐. Their state is abundant and numerous, and the population is sincere and true. There are many schools of the Great Vehicle. Their awesome ceremonies are uniform and orderly, and their receptacles and alms bowls make no sound.

Fifteen lisouth of the city there is Licha Shrine利刹寺. Within it there is a rock boot[s], and upon the rocks there is a footprint. Their customs tells this is a pratyeka-buddha's footprint. It has not been transmitted by Faxian, [I] suspect it is not a buddha's footprint.

Again it flows north-west, and pours into the He河. Precisely what the Classic speaks of as flowing north to pour into the Congling He蔥嶺河.

(The Nan He)

The Nan He南河 [“Southern He”] again goes east to pass north of Yutian State于闐國.

Mr. Shi's Records of the Western Regions says: The He River河水 flows east for 3 000 li, and arrives at Yutian于闐, and bends to flow north-east.

The Book of Han's Account of the Western Regions says: FromYutian于闐 and eastward, the rivers all flow east.

The Nan He南河 again goes north-east to pass north of Yumi State扜彌國, seated at Yumi City扜彌城. The distance west to Yutian于闐 is 390 li. The Nan He南河 again goes east to pass north of Jingjue State精絶國. The distance west to Yumi扜彌 is 460 li. The Nan He南河 again goes east to pass north of Qiemo State且末國. Again east, on the right side it meets with the Anouda Great River阿耨達大水.

(Qiemo)

Mr. Shi's Records of the Western Regions says: North-west of Anouda Mountain阿耨達山 there is a great river. It flows north to pour into the Laolan Sea牢蘭海. Its river flows north to pass the mountains south of Qiemo且末. Again north it passes west of Qiemo City且末城. The state is seated at Qiemo City且末城. The length west to Jingjue精絶 is 2 000 li, the distance east to Shanshan鄯善 is 720 li. They grow the Five Grains, and their customs are roughly similar to the Han.

He also says: The Qiemo He且末河 flows north-east to pass north of Qiemo且末. It again flows and to the left meets the Nan He南河. The met up flow to the east goes away, and passes through to become the Zhubin He注濱河.

(Shanshan)

The Zhubin He注濱河 again goes east to pass north of Shanshan State鄯善國, which is seated at Yixun City伊循城.

Formerly it was the territory of Loulan樓蘭. The King of Loulan樓蘭 was disrespectful to the Han. 4thYear of Yuanfeng [77 BC], Huo Guang dispatched the Overseer of Pingle, Fu Jiezi, to stab and kill him, and furthermore install the following king. Han also installed the former king's hostage son Weituqi as king, and altered the name of his state to Shanshan鄯善. The hundred officials held sacrifices for the road at the crosswise gate, and the King himself requested to the Son of Heaven, saying:

“Myself has been in Han for a long time, and fear to be harmed by the former king's sons. The state has Yixun City伊循城, and the soil and earth is fertile and pleasing. [I] wish to dispatch a commander to guard the fields and store up grain, and cause [me] to get to rely on the awesome honour.”

Thereupon he set up fields to use for garrisoning and comforting them.

Suo Mai of Dunhuang敦煌, courtesy name Yanyi, was talented and sharp. The Inspector, Mao Yi, petitioned he act as General of the Secondary Host, to command a thousand troops from Jiuquan酒泉 and Dunhuang敦煌 and enter, and arrive at Loulan's樓蘭 guarded fields. He erected a white building, and summoned troops from the three states of Shanshan鄯善, Yanqi焉耆, and Qiuci龜茲, a thousand each, to cut across the Zhubin He注濱河. At the day of cutting the He, the water exerted powerful spurts and the waves climbed to spread over the dikes. Mai in a strict voice said:

“When the king venerates the established moderation, the He's dikes do not overflow. When the king surpasses purest sincerity, the shouting tributaries do not flow. Water's potency has a godly clarity, both before and now.”

Mai personally prayed and worshipped, the water still did not diminish. Then he arranged the columns beating a cane, with the din of drums and tumultuous shouts, stabbing and shooting, they greatly fought for three days. The water then turned around and diminished, to pour and moisten, irrigate and spread out. The foreigners declared it godly. They greatly farmed for three years, and stored up grain in the millions, over-awing the submitting outer states.

Its river to the east pours into a marsh. The marsh is north of Loulan State樓蘭國 [at] the Yuni City扜泥城. Their customs speaks of it as the Eastern Old City東故城. The distance to Yang Pass陽關 is 1 600 li. The distance north-west to Wulei烏壘 is 1 785 li, until Moshan State墨山國 is 1 865 li. The distance north-west to Jushi is 1 890 li.

The soil and earth is sandy and saline with little farmlands, they look up to the grain in nearby states. The state produces jade, and there is much reeds, tamarisk willows, western poplar, and white grass. In the state on its eastern brink there is White Dragon Knoll白龍堆. It is short on water and grass, often jade issues out and clear the way, compensating for water and taking responsibility for the food, receiving and seeing off the Han envoys. For that reason their customs speaks of this marsh as the Laolan Sea牢蘭海.

Mr. Shi's Records of the Western Regions says: The Nan He南河 from east of Yutian于闐 to the north is 3 000 li. Arriving at Shanshan, it enters into the Laolan Sea牢蘭海.

6 notes

·

View notes